My Search For Alpine, Washington

Introduction

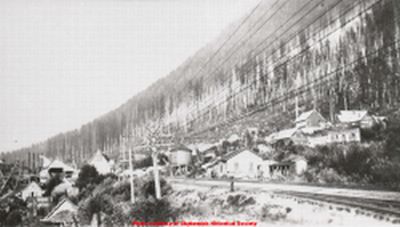

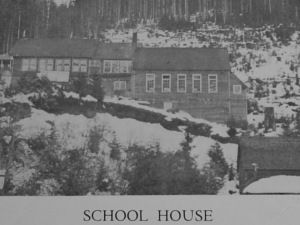

The storied ghost town of Alpine, Washington lay hidden in the second-growth forest of Washington's Cascade Mountains for 80 years on the northern slope of a ridge that extends from Mt Sawyer. Only in the last 4 years has Alpine been found again, and we have begun to map the remaining ruins. Alpine, Washington was abandoned in 1929; the buildings are gone, but we have so far found the foundations of the mill, the school, the social hall (built as the "Victory Hall" during World War I), the boarding house (which also housed the company offices and the post office, according to a 1926 map of Alpine), and 10 other buildings, some identified, some not. Our exploration of the site has covered only about 50% of the town; there is much yet to be found. 30 of us have participated in the exploration of the site, and 3 others have done substantial research to support the exploration of a place they may never see.

This web site will continue to grow as I add information, and, especially, photos. 8 photographers have contributed to this site, and there are external links to the photos of 3 other photographers. There remain several hundred photos for me to select from, and more have been taken that aren't yet available to me. At this moment (January 25, 2012) the story on this web site is many months behind actual events. This project has grown far beyond what it was intended to be. I originally intended to walk through Alpine and keep on walking; but this town and the ghosts of the memories of its people has seized me and not yet allowed me to go. This web site has become an online book, the equivalent of 150 paperback pages, with more than 100 external links to web sites that have information about Alpine, or to tangential eclectic sites that have information that may or may not interest someone who is looking for the definitive Alpine web site, but which have stories that are somehow linked. The story includes ghost towns, eerie events, and cemeteries. It also includes a history of the town and of its founder, Carl Lane Clemans, and more than a few mentions of history at Stanford University. It includes some of the adventures and misadventures of those of us who have tried and are trying to learn the forgotten story of this once thriving town.

The laughter of children once echoed in the Carroll Creek Valley in the middle of Alpine. At least 3 of those children were still alive in 2009, more than 80 years old. They have shared memories of Alpine with us, and given us information that we could never have known otherwise. It was more than a year after I began the search for Alpine that I met the first of these Alpiners. We had found 3, but we lost Bob Crawford on October 31, 2009. I hope there may be more Alpiners still alive who can tell us about the town they lived in, but we have only found 3. Nancy Cleveland and Anne Sekor have recorded the memories of these Alpine pioneers for posterity.

There are more than 50 photos on this web site. Most photos link to other pages and additional information if you just click on the photo.

I am still learning about Alpine, and I want to know more. If you have Alpine information, and are willing to share it, please contact me at tim@abarim.com. If you know someone who lived in Alpine, or someone who is the child or grandchild of someone who lived in Alpine, please contact me. Each has a story, and we would like to add those stories to the history of Alpine.

Some chapters of this site won't interest everyone. In fact probably no one will be interested in everything on the site. Not every chapter is directly about Alpine; some are about locations (such as Wellington) that are near by. Skip around to find what interests you. Look at the photos and click to the links from the photos. The chapter titles will give a clue to what in that chapter may interest each visitor. This isn't a book that must be read from beginning to end. Many of the chapters are still under construction and information is added as I find the time. Visitors point out errors, lost web links, and typos.

The owners of the 80 acres that encompass the ghost town of Alpine, Washington will have the final say; it is their property; but it is my hope that what is left of the little town of Alpine, Washington may be preserved and turned into an interpretive site that may be enjoyed by everyone. There is no formal organization to this end, but, in addition to the people who have participated in the exploration, dozens of people have contributed small amounts of money that has been used for some tools and gloves for the clearing operation, and for photocopying fragile records of events and irreplaceable photographs. The history of Alpine may not be complete. A number of us have begun to dream that we may preserve the remaining foundations and create a maze of gentle trails and information stations on the site of Alpine. The next or so will determine whether this will be a reality or just a pipe dream. A project of this size will cost a lot of money and require organization and a great deal of volunteer labor. If this interests you, I can be contacted at tim@abarim.com or at my work phone number 425 670 8167.

Also check out Matt Cawby's Alpine blog. And we now have a group in Yahoo Groups at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/AlpineWashington/

Several photos have been posted on the group site that aren't on this site, including an aerial photo of Alpine in 1930. There are also photos at the new FaceBook page http://www.facebook.com/pages/Alpine-WA/279532278821165

Avalanche

An avalanche blocked my path. The lower Iron Goat Trail, near Stevens Pass, Washington, was covered to a depth of more than 20 feet by snow, boulders, shattered trees, and the debris that an avalanche picks up as it roars down a mountainside. There were footprints in the snow. Someone had been foolish enough, or brave enough, to climb over the avalanche. My car was parked 2.5 miles behind me at the Martin Creek Trailhead; I had no incentive to climb over the avalanche and no desire to risk it. Nearly hidden under the avalanche was the concrete backwall of an old snowshed. The shed itself had long since rotted away and collapsed under the weight of 80 winters of neglect. Only the concrete backwall of the snowshed remained. The location of the avalanche that morning is a known avalanche chute, along a route that once was the Great Northern Railway. One hundred years ago the railroad had built a series of showsheds to protect the line from just this sort of accident. All but one of the snowsheds is now gone. The concrete backwalls stand as evidence of what was once there.

The avalanche had roared down the

southwest slope of Windy Peak, probably the deadliest mountain for avalanches in

the country, covering both the upper and lower Iron Goat Trails. Far more than 100 people

have died in avalanches on Windy Peak, most on what is now the upper Iron Goat Trail. Many of those lives were

lost when the railroad was operating, and the railroad hadn't used this route

since  early 1929 when the "new" 8-mile Cascade Tunnel had opened. But, over the

years, cross-country skiers, snowmobilers, and hikers had been at risk when

traveling in the shadow of Windy Peak. On this day I didn't think I was at risk

and I didn't expect an avalanche. It was a little past noon on the 31st of May,

2008. It was nearly summer and the air temperature was about 60 degrees. I don't

know how much earlier the avalanche had descended, and I hadn't heard

any roar. But it was a warning. This can be dangerous country, very dangerous in

Winter, but risky at all times of year.

early 1929 when the "new" 8-mile Cascade Tunnel had opened. But, over the

years, cross-country skiers, snowmobilers, and hikers had been at risk when

traveling in the shadow of Windy Peak. On this day I didn't think I was at risk

and I didn't expect an avalanche. It was a little past noon on the 31st of May,

2008. It was nearly summer and the air temperature was about 60 degrees. I don't

know how much earlier the avalanche had descended, and I hadn't heard

any roar. But it was a warning. This can be dangerous country, very dangerous in

Winter, but risky at all times of year.

It was another avalanche that had first interested me in this place. That earlier avalanche, the most deadly in U.S. history, struck the small town of Wellington, Washington in the very early morning of March 1, 1910. According to the official records, 96 people died in that avalanche when 2 Great Northern Railway trains, rotary snowplows, electric engines, and the Cascade Division Superintendent's personal cars were swept into the Tye River 150 feet below Wellington. It was the worst loss of life in a railroad disaster up to that time. Bob Kelly has a fine web site about the Wellington Avalanche at http://myplace.frontier.com/~mvmmvm/ In 2007 Gary Krist wrote an outstanding book, "The White Cascade", about the Wellington Avalanche. In 2009 Martin Burwash wrote "Vis Major", a novel, but a novel that stays very close to the real history, and the real people of the Wellington Avalanche. The Iron Goat Trail now follows the route of the old Great Northern Railway for 9 miles from the old Cascade Tunnel at what once was the town of Wellington, west of Stevens Pass, Washington, to Scenic Hot Springs. In its 9 miles the Iron Goat Trail has an elevation gain of 1000 feet.

I first learned about the Wellington disaster from a small

entry in the 1958 World Almanac. I was 11 years old. For years I didn't learn

anything more. I didn't even know exactly where Wellington might have been. The

Great Northern Railway had renamed the depot as Tye, to erase the memory of the

disaster, and abandoned that route completely in 1929. The grandfather of one of

my high school friends had lived in Tye for 3 years while working on the "new" 8

mile Cascade Tunnel from 1926 to 1929. He had never heard of Wellington although

he lived in it or near it for 3 years. From the Stevens Pass Highway I could see

what I now know to have been snowsheds that have gradually collapsed over the years.

It was 2001 before I learned the exact location of Wellington. It was 2006

before I visited Wellington for the first time, and walked the upper Iron Goat Trail.

I first learned about the Wellington disaster from a small

entry in the 1958 World Almanac. I was 11 years old. For years I didn't learn

anything more. I didn't even know exactly where Wellington might have been. The

Great Northern Railway had renamed the depot as Tye, to erase the memory of the

disaster, and abandoned that route completely in 1929. The grandfather of one of

my high school friends had lived in Tye for 3 years while working on the "new" 8

mile Cascade Tunnel from 1926 to 1929. He had never heard of Wellington although

he lived in it or near it for 3 years. From the Stevens Pass Highway I could see

what I now know to have been snowsheds that have gradually collapsed over the years.

It was 2001 before I learned the exact location of Wellington. It was 2006

before I visited Wellington for the first time, and walked the upper Iron Goat Trail.

This day in May 2008 was my first walk on the lower Iron Goat Trail. I had walked parts of the upper trail 6 or 7 times, but this morning I had decided to walk the lower trail from Martin Creek to the parking lot at the Windy Point trailhead near Scenic Hot Springs. Blocked by the avalanche, I turned back to walk the 2.5 miles to my car. It hadn't been a useless day. I had seen the famous Twin Tunnels of the lower trail, and I had visited the site of Corea, once a stop on the Great Northern Railway. Near Corea 3 original telegraph poles still stood, having survived 80 Cascade Mountain winters.

As I walked back to my car I thought about the trail and the

railroad. I had now visited every station location between Cascade Station and

Scenic. I had never really visited Scenic, but I had driven by it a hundred

times or more. I decided that I would visit every station back down from the

mountains to Puget Sound and my home in Edmonds. Scenic was nearby, but I was

hungry and I turned west toward Skykomish and the Cascadia Inn, where I would devour a

Cadia Burger. In June I intended to visit the tiny station at Scenic, still used by

the Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad, the successor to the Great Northern

Railway.

In June I did visit Scenic. It really isn't much of a place.

The hot springs have been closed for many years, and the old resort hotel has

been gone just about as long as the old railroad route. The owner of the hot springs has marked it "No Trespassing" - probably because of liability concerns. The only interest at

Scenic is that a train is often waiting for its turn to go through the "new" 7.8

mile Cascade Tunnel. It takes a while for the tunnel to clear of exhaust gases

from the diesel engines. Powerful fans at the Berne (east) entrance to the

tunnel expel the exhaust fumes. Otherwise the tunnel could be a dangerous place

to travel. The original 3 mile tunnel from Cascade Station to Wellington had

been dangerous in the era of steam engines, and some trainmen (and probably a hobo or two) had been

asphyxiated by the noxious fumes of coal-burning steam engines. Great Northern had electrified the original tunnel in 1909. Electric

engines pulled the trains through the tunnel - then steam would take over again.

The "new" tunnel had been electrified until July 31, 1956. On that day #5018 made the last electrified trip through the tunnel.

Now, for more than 50 years, diesels have carried the load. Often 5 or 6 diesel engines pull a train up the slope and through the Cascade Mountains. Diesels are more efficient for the railroad because it is no longer necessary to waste time coupling electric engines into and out of trains to move through the mountains, and extra train crews at Skykomish and Leavenworth are no longer necessary. The longer tunnel saved the railroad time and money, and it avoided the most dangerous stretch of railroad. The "new" tunnel is nearly 1000 feet lower than the old tunnel. The hazard of snow is greatly reduced by the "new" tunnel, and the hazard of avalanche is almost non-existent.

Corea in May. Scenic in June. In July it would be Alpine. Or would it? First I had to find Alpine. Every old Great Northern station site that I had visited had either been close to Highway 2, which is the Stevens Pass Highway, or on the Iron Goat Trail. Alpine was neither. In fact Alpine didn't seem to be anywhere. The town of Alpine was bigger than any of the other towns and stations that I had visited. Alpine was the biggest town on the Great Northern Railway in the 50 miles between Leavenworth and Skykomish. Skykomish still survives, and Leavenworth thrives despite the loss of the railroad. Alpine didn't survive. It was too high, and too remote, and too far off the highway when the common mode of transportation changed from railroads to highways in the 1920s. Few of us now will drive a mile off the interstate. In 1929 almost no one would drive one mile from the highway and an elevation gain of 500 feet. Alpine died and its location was lost for 80 years.

In 1924 Alpine had been the last town of the "passable highway". On October 31, 1924 the first car to drive over Stevens Pass reached Alpine where is was winched up to the railroad tracks by the Alpine mill. From there the car drove on the railroad ties to Tye and then along the old railroad switchbacks to the Stevens Pass summit. 1 By July 1925 the Stevens Pass Scenic Highway was open and Alpine was a mile off the highway, and within 4 years Alpine had been abandoned. The ghost town of Alpine was somewhere along the present-day BNSF railroad line, but there was apparently no longer a road into the town. The prospect of walking 3 miles along the railroad to find what might not be there was a not very inviting prospect. I used up several weekends testing every road and cowtrail that might get close. No luck. I checked the internet. On the internet I found an interesting web site about Alpine by Patrick Burns, who had also tried to find Alpine, but he had no answer to its location. I had tried the same road he had tried, and, like him, found the prospect of walking the rails for 2 or 3 miles not to my liking.

Patrick Burns is Professor Emeritus at Valdosta State University in Valdosta, Georgia. Patrick is an Edmonds, Washington native, the same town I now call home, and in 2009 he moved back to Puget Sound, settling in Mukilteo. But at that time Pat was still living in Georgia. His web site, Alpine Pursuit introduced me for the first time to the work of Seattle author Mary Daheim. Daheim has written a series of mystery books that take place in the mythical town of Alpine, Washington. Except Daheim's Alpine isn't completely mythical. Mary Daheim's grandparents lived many years in Alpine. Mary's mother grew up in Alpine and her parents lived in Alpine during their early married life. Mary Daheim has brought the town of Alpine back to life in her Emma Lord series of mysteries. In the books, Emma Lord is the publisher of the Alpine Advocate newspaper in the town of Alpine that in some alternate universe has survived as a viable town to the present day, and is now the county seat of mythical Skykomish County, Washington. I was not in the habit of reading mysteries, or any fiction for that matter, and I had not heard of Mary Daheim or her books. I did send an email to Pat Burns in which I said, "I am glad there is at least one person in the world who is as big an idiot as I am." Pat didn't take offense, he understood what I meant about this strange obsession when one catches the "Alpine flu".

Apparently I was the only person in the Seattle area who didn't know Mary Daheim and had not read at least one book in the Alpine Advocate series. Jan Kavadas promptly dropped 3 books of the series on my desk to read. I read Alpine Journey and really didn't care for it. Maybe I didn't like Alpine Journey because it didn't happen in Alpine. Of all the books in the series, Alpine Journey has the least to do with Alpine. Alpine Journey doesn't even take place in Washington; almost the entire book takes place in Cannon Beach, Oregon, about as un-Alpine a place as you may find in the Pacific Northwest. A few weeks later, while visiting my friend Bill Longbrake, Bill told me that he, renamed for fiction as Bob Lambrecht, was one of the characters in book 6, Alpine Fury. I then borrowed and read Alpine Fury, and, partly because I could recognize Bill and one of the other characters, I enjoyed the book somewhat more. Fran Uchida, who loaned me Alpine Fury, and Martha Longbrake, Bill's wife and devoted Mary Daheim fan, both suggested that I would enjoy the books more if I started at the beginning with the Alpine Advocate, read through the series, and get to know the characters as they develop. I bought a copy of Alpine Advocate and started there. The advice was correct. Like the Yellow Brick Road it is usually best to start at the beginning. I began to enjoy the books, but this didn't get me any closer to finding Alpine. At the beginning of Alpine Advocate, Mary Daheim included in an Author's Note a brief description of the real Alpine and its founder Carl Lane Clemans, and dedicated the book. "To all those who lived the real Alpine story, and in the process, created a legend. These courageous men and women embodied the spirit of the Pacific Northwest." 2 I would later find that Clemans had been a remarkable man, better known for many things than just the founder of a small town in the Washington Cascades. Mary Daheim has almost single-handedly kept the name of Alpine alive for nearly 2 decades. Now it was up to me to find Alpine if it was really there to find. I was warned that there was little left of the town. The Wikipedia listing says that all that remains of Alpine are 2 cornerstones of the mill. Maybe that would be all that I would find, but by now I was determined to find it. If you have visited a rain forest you know how difficult it may be to find anything, even if you know that it is there. In the dry Southwest the buildings of a ghost town may linger for centuries; in the wet of a Pacific Northwest rain forest a town may rot away in a couple of generations. That was the challenge. What to do now?

Bob Kelly, at the Skykomish

Museum, gave me a railroad milepost at 1723.5 (measured from the beginning

of the old Great Northern Railway in St Paul), but that was 2 miles from the

nearest way in to Alpine that I had found. In early August my daughter, Chrissy,

accompanied me on road searches. That she barely tolerated old dad's eccentricities

was more like it, and she went along because my daughters are always afraid that dad will drive off a road 50 miles from nowhere and the body won't be found until the next year. On the Foss River Road, just past where the road crosses the

Foss River on a one-lane bridge, was a road that looked promising, Forest

Service Road 6180. After traveling east less than 2 miles our journey on that

road came to an end at a "Private Property" sign. Many months later I learned

that this old, weary, poorly-maintained, dirt road has a story to tell.

According to King

County tax records, this old road, east from Foss River, is the original

Stevens Pass Scenic Highway, abandoned by Washington State in 1940. Bob Kelly

says that oldtimers in Skykomish remembered driving that road to dances in

Alpine. But for me the road no longer went as far as Alpine. Too bad. Chrissy

and I climbed up the slope next to the Foss River trestle. The railroad milepost

read 1728.2 - we wouldn't get into Alpine from there. I didn't know that help

was nearby, virtually in the noon shadow of the Foss River trestle in the form

of Pat Casey, the Foss River Hermit. I wouldn't meet Pat for another month.

Bob Kelly, at the Skykomish

Museum, gave me a railroad milepost at 1723.5 (measured from the beginning

of the old Great Northern Railway in St Paul), but that was 2 miles from the

nearest way in to Alpine that I had found. In early August my daughter, Chrissy,

accompanied me on road searches. That she barely tolerated old dad's eccentricities

was more like it, and she went along because my daughters are always afraid that dad will drive off a road 50 miles from nowhere and the body won't be found until the next year. On the Foss River Road, just past where the road crosses the

Foss River on a one-lane bridge, was a road that looked promising, Forest

Service Road 6180. After traveling east less than 2 miles our journey on that

road came to an end at a "Private Property" sign. Many months later I learned

that this old, weary, poorly-maintained, dirt road has a story to tell.

According to King

County tax records, this old road, east from Foss River, is the original

Stevens Pass Scenic Highway, abandoned by Washington State in 1940. Bob Kelly

says that oldtimers in Skykomish remembered driving that road to dances in

Alpine. But for me the road no longer went as far as Alpine. Too bad. Chrissy

and I climbed up the slope next to the Foss River trestle. The railroad milepost

read 1728.2 - we wouldn't get into Alpine from there. I didn't know that help

was nearby, virtually in the noon shadow of the Foss River trestle in the form

of Pat Casey, the Foss River Hermit. I wouldn't meet Pat for another month.

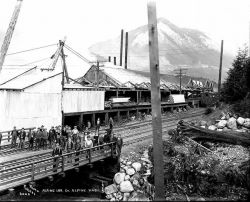

The Alpine depot had originally been named Nippon. Japanese railroad workers may have lived in Nippon while the railroad was constructed in the early 1890s. Or the name Nippon may have been just another international name applied to the Great Northern Railway. James Hill, the "Empire Builder" as he was later known, believed that he could transport the goods of Asia and Europe across a North American railroad link. Goods could travel from Seattle to New York in days, instead of the weeks or months that it would take a ship to travel the distance. The Panama Canal didn't exist in 1890. European and Pacific names dotted the Great Northern Railway. In Washington there were Nippon, Tokio, Corea, Tonga, Berlin, Wellington, and Krupp. It is doubtful that the towns were inhabited by Japanese, Koreans, Polynesians, English, and Germans. It is more likely that the name was just a name in the worldwide vocabulary of the Great Northern. The name on the Nippon Depot wasn't changed to Alpine until 1914. The Post Office had called the town Alpine for postal purposes since the founding of the town in April 1910. Why, don't know? But Carl Clemans, acting as postmaster of Alpine, stated it well in a letter to M. J. Costello, traffic manager for the Great Northern Railway, when he said, "We would therefore respectfully request that the name of the station be changed to "Alpine" which on account of the character of the country seems a fitting appellation." 3 We do know that the Post Office declined the name of Nippon because there was already a Nippon Postal Office in Seattle. Maybe Carl Clemans had used the same reasoning in selecting the Alpine for the Post Office name when he discovered in 1910 that it couldn't be called Nippon.

Clemans was more than the postmaster of Alpine. Alpine was a company town and Carl Clemans ran the company. But the company town image that most of us envision apparently doesn't fit in the case of Alpine. Copies of several of the Alpine annual reports still exist at the Skykomish Museum. In those reports are the record of births, deaths, and marriages, the date of the last snow visible on Mount Baldy across the Tye River valley, the date of the first new snow on Baldy, and the usual company records that you would expect in an annual report. In those annual reports Mr Clemans seems to take great pride in the success of his former employees. He proudly talks about former employees who are now mill owners or lumber company owners themselves, or who have moved to other occupations in the city. There is a sense, almost, of a parent talking about his sons who have gone on and succeeded in the world.

The annual reports were given to attendees at the Alpine annual banquet. The name of the company remained the Nippon Lumber Company for many years after the depot was renamed Alpine, but in 1920 the name of the company itself was changed to the Alpine Lumber Company. Throughout the twenties the company, the depot, the post office, and the town itself went by the name of Alpine. Then the twenties ended and so did the town, almost lost to memory. I wanted to find Alpine, whatever little might remain. In a rain forest that might be little or nothing. I had gone looking for the town of Franklin in southeast King County a number of years ago and had found almost nothing. I might find almost nothing of Alpine, but once I had found it I could move on down the Tye and Sky River valleys to the locations of old Great Northern Railway stops at Tonga and Berlin/Miller River and Grotto and Baring and Halford and Heybrook.

August Visit to the Ghosts of Wellington and Cascade Station

On August 17, 2008 I temporarily abandoned my search for Alpine.

Melissa Logstrom accompanied me in a visit to  Wellington and Cascade Station.

Wellington was 12 railroad miles east of Alpine, and about 6 direct miles northeast of Alpine. Cascade Station was 3 miles further east. A railroad can't climb much more than 100 feet per mile. Alpine is at 1800 feet and Wellington is at 3000 feet. To get from Alpine to Wellington the Great Northern Railway needed 12 miles of track. To accomplish this the Great Northern installed a big curve at Scenic that turned the track back to the west. From Scenic the Great Northern went 3 miles to Martin Creek and turned back to the east in the "Horseshoe Tunnel". This added the additional 6 miles that the railroad required to gain the full elevation from Alpine to Wellington. For 3 miles the railroad went west to go east, but the railroad direction was always considered to be "east". The compass direction from Scenic to Corea, and then to Martin Creek, might be west by north, but the engineer and conductor understood the railroad directions that the route was always east.

Wellington and Cascade Station.

Wellington was 12 railroad miles east of Alpine, and about 6 direct miles northeast of Alpine. Cascade Station was 3 miles further east. A railroad can't climb much more than 100 feet per mile. Alpine is at 1800 feet and Wellington is at 3000 feet. To get from Alpine to Wellington the Great Northern Railway needed 12 miles of track. To accomplish this the Great Northern installed a big curve at Scenic that turned the track back to the west. From Scenic the Great Northern went 3 miles to Martin Creek and turned back to the east in the "Horseshoe Tunnel". This added the additional 6 miles that the railroad required to gain the full elevation from Alpine to Wellington. For 3 miles the railroad went west to go east, but the railroad direction was always considered to be "east". The compass direction from Scenic to Corea, and then to Martin Creek, might be west by north, but the engineer and conductor understood the railroad directions that the route was always east.

From 1893 to 1929 Wellington and Cascade Station had been the Great Northern Railway stations on either side of Stevens Pass. Wellington was the west station and Cascade Station was on the east. From 1893 to 1900 the two stations had been connected by a series of switchbacks. In 1900 a 3-mile tunnel under Stevens Pass was completed, sharply reducing the time between the two stations, but increasing the danger. Smoke from steam engines accumulated in the tunnel, making it nearly impossible to breathe. Heat built up in the engine cabs because there was no place for it to dissipate. An unknown number of train crewmen, and probably some hobos died of asphyxiation in the tunnel.

The Great Northern Railway had a reputation of being easy on hobos. Other railroads would treat hobos badly if they caught them. "What they said Jim Hill said, 'Bums built it, bums can ride it.' " 4 That Great Northern welcome mat for hobos may have ended badly for some in the heat and choking smoke of the old Cascade Tunnel.

On another occasion

"a train carrying over 100 passengers broke down in the tunnel. While attempting to fix the problem, The engineer, fireman, and conductor all succumbed to the fumes and collapsed. As the passenger cars slowly began to fill with gas, an off-duty fireman named Abbott, riding as a passenger, fought his way forward to the locomotive and released the brakes. The train proceeded to roll downgrade, gathering momentum until it shot backward out of the tunnel at Wellington. Abbott was still sentient enough to trigger the emergency brakes. The train screeched to a stop in the Wellington yard, its crew and most of its passengers unconscious but still very much alive" 5

The danger of the Cascade Tunnel finally forced the Great Northern Railway to invest in electric locomotives. The electrics went into service in July 1909. There were some problems. Sometimes an electric locomotive would fail and the steam locomotives would be pressed into service. Even so, the electrification of the Cascade Tunnel from Wellington to Cascade Station was a measurable improvement in safety and comfort for train crews and Great Northern passengers.

There is an irony in the suffocating smoke and hellish heat of

the Cascade Tunnel when used by steam  locomotives. I have entered the portals of

the

locomotives. I have entered the portals of

the  Cascade Tunnel about 10 times. I was never brave, or foolish, enough to walk

all the way through from Wellington to Cascade Station.

The tunnel always looked too dangerous and likely to fall down for my taste. The

tunnel is cold and wet and miserable, in stark contrast to the vision of

oppressive heat and smoke that accompanied steam locomotives. Water runs

continuously in the drainage ditches on either side of the old trackbed. The

tunnel roof finally did collapse near the Wellington end in the Spring of 2008,

and fencing prevents visitors from getting too close to the tunnel portal. It is

now subject to sudden releases of water from behind the debris of the collapsed

roof. It is dangerous; it is fenced off for good reason; don't go near the west

portal.

Cascade Tunnel about 10 times. I was never brave, or foolish, enough to walk

all the way through from Wellington to Cascade Station.

The tunnel always looked too dangerous and likely to fall down for my taste. The

tunnel is cold and wet and miserable, in stark contrast to the vision of

oppressive heat and smoke that accompanied steam locomotives. Water runs

continuously in the drainage ditches on either side of the old trackbed. The

tunnel roof finally did collapse near the Wellington end in the Spring of 2008,

and fencing prevents visitors from getting too close to the tunnel portal. It is

now subject to sudden releases of water from behind the debris of the collapsed

roof. It is dangerous; it is fenced off for good reason; don't go near the west

portal.

I have met people who walked through the tunnel when it was possible. On one occasion, as I stood in the west portal at Wellington, voices seemed to materialize inside the tunnel and then a woman and 6 children appeared out of the darkness. They weren't apparitions - they had started walking at the Cascade Station (east) portal of the tunnel and had walked nearly 3 miles to the Wellington (west) portal. Their car was at Cascade Station and they had little choice but to turn around and walk back through the tunnel. The distance was 3 miles through the tunnel and about 7 via the Old Cascade Highway and US2 through Stevens Pass. I didn't have a big enough car to offer them all a ride.

Wellington and the original Stevens Pass Tunnel are reputed to be haunted. Joni Schinske, Museum Director for the Edmonds-South Snohomish County Historical Society, said of Wellington. "I went to Wellington with no preconceptions. It was my second trip there and my interest was strictly historical. I could feel a presence that made me uneasy. Then I heard a steam whistle. Even if there was a train on the lower railroad, a steam whistle doesn't sound like a diesel. I haven't been back to Wellington since."6 Joni is not the first to believe that Wellington and the Cascade Tunnel are haunted. Some claim to have seen or photographed orbs of light in the old Cascade Tunnel and in the concrete snowshed that now covers the location of the Wellington Avalanche, west of the old townsite.

I had visited the tunnel portals at Wellington, or the Cascade Station side of the Cascade Tunnel about 10 times before this trip. Melissa and I walked along the Upper Iron Goat Trail as far as the west end of the concrete snowshed that was built in 1911 to protect the railroad from a possible repeat of the 1910 avalanche. Melissa had not been to Wellington before and was interested in what I knew, and was intently reading the information at the interpretive stations. Melissa had read Gary Krist's book, The White Cascade, as had I. We had it in the car, and a couple of old photos that I had printed from Bob Kelly's web site. We used the maps and photos as references for our tour of old Wellington, in addition to the interpretive stations. No buildings remain; those were all burned down in 1929, as were the buildings in Cascade Station, Berne (east of Cascade Station), and probably Embro and Corea as well. Alpine may have been burned at about the same time, but for different reasons and it wasn't burned by the railroad. At Wellington the concrete abutments of the old Haskell Creek bridge remain, and the concrete foundations of the water tower, the coaling tower, and the foundation of the repair shed for the rotary snowplows and electric engines. The repair shed was a little bigger than most sheds; it was about 300 feet long and had some resemblance to a Grease Monkey in that the mechanics could get under the rotaries and snowplows to service the units from underneath.

Melissa was disappointed that we couldn't approach the west

portal of the old Cascade Tunnel. When we had walked around Wellington for an

hour or so, I drove us east to the Cascade Station portal. It is still

accessible, and probably will remain accessible for a few more years. The old

tunnel is lower on the Wellington (west) end than it is on the Cascade Station

(east) end. Water in the tunnel runs downhill to Wellington from Cascade

Station. There is no danger of a sudden release of water at the Cascade Station

site. The Cascade Station side of the tunnel is also probably in somewhat better

shape than the Wellington end. Only 3 miles apart, the Cascade Station portal is

in the "rain shadow" of the Cascade Mountains, and receives noticeably less snow

and rain than the Wellington end. The tunnel is

still dangerous at the east portal, just less dangerous than the west end. I am

just as unwilling to walk very far into the east portal as I was into the west.

It is just too dangerous.

accessible, and probably will remain accessible for a few more years. The old

tunnel is lower on the Wellington (west) end than it is on the Cascade Station

(east) end. Water in the tunnel runs downhill to Wellington from Cascade

Station. There is no danger of a sudden release of water at the Cascade Station

site. The Cascade Station side of the tunnel is also probably in somewhat better

shape than the Wellington end. Only 3 miles apart, the Cascade Station portal is

in the "rain shadow" of the Cascade Mountains, and receives noticeably less snow

and rain than the Wellington end. The tunnel is

still dangerous at the east portal, just less dangerous than the west end. I am

just as unwilling to walk very far into the east portal as I was into the west.

It is just too dangerous.

Nevertheless we did venture a few feet into the east portal. It sounded like someone, or a number of people, was working inside the tunnel. There were hammering noises, or construction noises, but we didn't see anyone or any worklights. There should have been no one there, and there certainly should not have been any work going on. I had been in the two portals a combined total of about 10 times; I had never heard anything. The tunnel was usually quiet except for water, dripping from the ceiling and running in the ditches, and the voices of visitors. This was the first time that I was ever uncomfortable in the tunnel. I wanted to get away. Melissa, however, was enjoying herself immensely, snapping photographs of the tunnel and enjoying the moment at a place she had wanted to see for a long time. Eventually we walked back to my car and drove down the mountain to a pleasant early dinner at the Cascadia in Skykomish. After dinner Melissa humored me by allowing me to take a few of the backroads home instead of the highway. In Startup, we found that the road that is now called the Sultan-Startup Road was certainly part of the old Stevens Pass Scenic Highway. On the Startup side of the Wallace River the road turns sharply back on itself to go up to Highway 2. We could see where a bridge had once spanned the Wallace River at that point. On the Sultan side of the river we could see where the new road crosses the route of the old road as the old road more closely followed the line of the river than the highway does now.

The surprise about our trip to Wellington and Cascade Station

came 2 weeks later when Melissa downloaded the photos onto her computer and

looked at them. Visible in one of the photos is a famous Cascade Tunnel "orb".

These have appeared in photos taken in the old Cascade Tunnel and in the

concrete snowshed at Wellington. I had never personally seen one, and I

certainly hadn't seen any that day as we stood in the east portal. But there in

the photo is an "orb". A raindrop maybe? Except it wasn't raining; it was gray

day and it wasn't a reflection of a sunbeam either. A drip from the ceiling of

the tunnel? This is more plausible, and we wouldn't necessarily have heard it

with the pounding noises in the tunnel. Ah, those noises. What were they? There

were no other cars in the vicinity that day. Someone could have walked from a

cabin nearby, but we didn't see anyone. The tunnel isn't exactly a gathering

place, except for eccentrics, like me. What was the  noise and did it have

something to do with the "orb"? Some have metaphysical answers to the "orbs" -

ghosts and such. And maybe they are right - I was uncomfortable that day.

But I like hard, tangible, scientific, answers, and ghosts are definitely not

hard, tangible, scientific, answers. The mystery deepened a few days later when

Melissa enlarged the portion of the photo containing the "orb". In the

enlargement the "orb" seems to take on facial features - demonic, maybe, or

otherworldly. One viewer thought the image looked like a miner's hat with two lights, perhaps the ghost of one of the men who built the tunnel. All these thoughts are definitely beyond the type of scientific answer I would like to

see.

noise and did it have

something to do with the "orb"? Some have metaphysical answers to the "orbs" -

ghosts and such. And maybe they are right - I was uncomfortable that day.

But I like hard, tangible, scientific, answers, and ghosts are definitely not

hard, tangible, scientific, answers. The mystery deepened a few days later when

Melissa enlarged the portion of the photo containing the "orb". In the

enlargement the "orb" seems to take on facial features - demonic, maybe, or

otherworldly. One viewer thought the image looked like a miner's hat with two lights, perhaps the ghost of one of the men who built the tunnel. All these thoughts are definitely beyond the type of scientific answer I would like to

see.  But it is also an answer that will need to wait. I wanted to get back to

the search for Alpine. The mysterious construction noises that Melissa and I heard in the tunnel when there was no construction going on; the whistle of a steam engine that Joni had heard when there was no steam engine; the Cascade Tunnel orbs of light when there was no source of light. These are mysteries for someone to solve, but it probably won't be me. Alpine is enough of a mystery.

But it is also an answer that will need to wait. I wanted to get back to

the search for Alpine. The mysterious construction noises that Melissa and I heard in the tunnel when there was no construction going on; the whistle of a steam engine that Joni had heard when there was no steam engine; the Cascade Tunnel orbs of light when there was no source of light. These are mysteries for someone to solve, but it probably won't be me. Alpine is enough of a mystery.

We went back to Cascade Station 2 years later on August 17, 2010. Melissa and I were joined by Brian Harris, Levi Logstrom, Jenna Perry-Zapara, Matt Cawby, and Donna Beaudry. Melissa and Matt got some lovely "orb" photos. All of the photo orbs taken that day can be identified as lens reflected light. The prismatic effect is beautiful, but it is nothing like the photos Melissa took in 2008. Prismatic photo orbs can be duplicated in almost any dark, damp environment. Whatever it is that appeared in Melissa's photos in 2008 wasn't replicated. The photo to the left shows 3 orbs. Click on it to see an enlargement. Then compare it to the enlargement of the photo on the right taken at the same location 2 years earlier.

Alpine shares a bit of history with Cascade Station and Wellington and their ghosts. When the avalanche devastated Wellington on March 1, 1910 the nearest working telegraph was at Nippon depot. James H. O'Neill walked through 3 miles of 3-foot deep snow from Scenic to reach Nippon. The message that alerted the Great Northern Railway, and the world, of the deadliest avalanche in United States history, and one of the worst railroad disasters of all time, was sent from Nippon depot. 4 years later the Nippon depot was renamed Alpine to correspond with the post office name of the town that had grown up around the saw mill.

Great Northern Day in Skykomish

Each year in September the Skykomish Historical Society and the Great Northern Railway Historical Society sponsor "Great Northern Day" on a Saturday. Veterans of the Great Northern Railway, railfans, and anybody who has an interest gather in the small museum in Skykomish, Washington to talk about the history of the railroad. The Great Northern Railway ceased to exist in 1970, nearly 40 years ago, and the number of railroad veterans is smaller every year. Some who come are model railroaders in search of information that will make their model railroad layout accurate in every detail. Some are people who like to take pictures of trains, and like to see old pictures of old trains. Some, like me, are interested in the history - history of the railroad and history of the towns and people who once lived there. We gather in Skykomish; in 2008 the gathering was on September 13. Skykomish was once an important stop on the Great Northern Railway. Electric engines were connected to trains in Skykomish to pull the trains through the "new" Cascade Tunnel. A power plant to electrify the railroad by converting the AC from the power grid to DC for the electric motors once stood in Skykomish. It is long gone, and the roundhouse is long gone, and almost everything else is long gone. More than 2000 people once lived in Skykomish - fewer than 300 live there now. But a renaissance may be at hand.

Skykomish is in the process of moving almost the entire town. Actually the downtown is being moved out of its space and moved back again. During the time that the Great Northern Railway used Skykomish as its  west Cascade headquarter, there was oil stored in tanks. Those tanks leaked

west Cascade headquarter, there was oil stored in tanks. Those tanks leaked  into the soil and, ultimately, into the south fork of the Skykomish River. In 2006 a project began to remove the oil and clean the soil. To accomplish this end the buildings in the town must be moved from the locations where they have stood for 100 years or more. After the contamination in the soil is removed the buildings are placed back in the original positions on new foundations. The McEvoy house, which stands next to the Cascadia, looks to be in the best condition it has seen in 100 years. The project has been a strain on Skykomish and Skykomish businesses. If Skykomish survives the move, the town may be in the best condition that it has ever been. A new "Town Center" is planned for Skykomish. The "Town Center" will include vintage Great Northern Railway engines and cars. The old Great Northern depot will move back near its original location on the south side of the railroad tracks.

into the soil and, ultimately, into the south fork of the Skykomish River. In 2006 a project began to remove the oil and clean the soil. To accomplish this end the buildings in the town must be moved from the locations where they have stood for 100 years or more. After the contamination in the soil is removed the buildings are placed back in the original positions on new foundations. The McEvoy house, which stands next to the Cascadia, looks to be in the best condition it has seen in 100 years. The project has been a strain on Skykomish and Skykomish businesses. If Skykomish survives the move, the town may be in the best condition that it has ever been. A new "Town Center" is planned for Skykomish. The "Town Center" will include vintage Great Northern Railway engines and cars. The old Great Northern depot will move back near its original location on the south side of the railroad tracks.

Sky lives on into a 2nd century. The other towns of the upper Sky Valley - Heybrook, Halford, Baring, Grotto, Miller River (Berlin), Tye (Wellington), Corea, Scenic (Madison), Embro (Alvin), and Alpine are gone or much reduced in size. Index, at the confluence of the North and South Forks of the Skykomish River is also reviving some. Index has purchased Heybrook Ridge to the south and the granite "Climbing Wall" on the north, to preserve the character and appearance of the town. The combined effort to buy those assets cost nearly 2 million dollars, and will continue to need financial donations for some years to come to properly maintain the assets. Index has at least one other worthy project that isn't yet complete. The Bush House was a well-known hotel and restaurant from 1898 until the turn of the millennium. Reputedly, 3 United States Presidents have stayed there. The record isn't entirely clear on the first 2, but President Truman certainly stayed there during his campaign in 1948. The Bush House is now in a state of near collapse; it will be a shame if it is not preserved, but the cost for it will certainly run more than 1 million dollars to repair. I hope that Index may find the energy to preserve this portion of its heritage. I have never stayed in the Bush House, but I and my family enjoyed several wonderful dinners there during the 1980s and 1990s.

If we go ahead with a project to preserve Alpine from further destruction by the forest and weather, it will probably cost an amount similar to what Index has spent on their projects.

But I have gotten ahead of the story. I had begun to search for Alpine in June of 2008 and in mid-September 2008 I still hadn't found it. I hoped that someone would be able to help me find Alpine. In that I was almost successful at Great Northern Day, and I had a chance to have enjoyable conversations with a number of people.

Several people suggested that I talk to Pat Casey. Pat is known as the "Foss River Hermit". He lives well up the Foss River Road, near the Foss River trestle of the Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad. The Foss River trestle was built by the Great Northern Railway, the predecessor of the BNSF. I called Pat Casey a few days later and met him in Skykomish the next week. With Pat I walked along the BNSF railroad tracks to the site of the Tonga Station on the old Great Northern. Pat owns the southeast corner of the old Tonga townsite, but most of it is owned by Longview Fibre. When we walked the land in September 2008 it had already been surveyed in preparation for logging. At the site of the old depot we found bricks, broken crockery, and the remains of what appeared to be at least 2 wood stoves. Whatever else may be under the growth will probably be crushed by heavy equipment logging the area. That will be a shame. But Pat had never visited Alpine in the 45 years that he had owned a place on Foss River and didn't know exactly where it might be or how to get to it. Pat did have a suggestion. In Startup, at the little white church that was now an art gallery, I would find Bill Schlicker. He owned property in the general vicinity of Alpine. If he didn't own Alpine he would probably know who did own it. Pat also mentioned his brother-in-law, Jack Christensen, who lives in Edmonds. Jack is a former Northern Pacific and BNSF engineer. He is a noted artist, usually painting railroad scenes, and as a local railroad historian he often speaks to groups about railroading. Jack is also my neighbor, only about 8 houses down 9th Avenue, but we had never met. He is a very interesting man, but he really had no information about the town of Alpine.

Several people at Great Northern Day in Skykomish also suggested that I talk to Ted Cleveland. I had met Ted 2 years before when he had been one of the speakers at Great Northern Day. Ted was born in Skykomish. He worked for the Great Northern Railway. He had been the fireman on the last electric engine that had left Skykomish to pull a train through the Cascade Tunnel on May 31, 1956. Ted had been mayor of Skykomish twice. When I called Ted he remembered Alpine. He had ridden the train through the vicinity of Alpine hundreds of times. But more than that, he remembered Alpine. He remembered seeing Alpine as a boy, when he was 5 or 6 years old, he had walked into Alpine with his father. The buildings had been empty. There was no one there but the wood and concrete evidence that this had once been something. But as to how to easily get there now he didn't have an answer. Ted did suggest, as Pat Casey had, that I talk to Bill Schlicker in Startup.

It was the last person I met at Great Northern Day, Matt Cawby, who had the most immediate interest in Alpine. Matt is a photographer from Mountlake Terrace, WA. I quickly infected Matt with the Alpine Flu and within 2 weeks he found Alpine and took photos which are at his web site. Matt is noted for photographing Boeing jets, but he also is interested in trains and the history of the Great Northern Railway. He and his dog walked into Alpine and took pictures, then matched the present day photos to archive photos at the Skykomish Museum. Unfortunately it was a few more days before Matt let me know how to find, and more importantly how to get into, Alpine. By then I had visited the little white church in Startup, talked to Bill Schlicker, gotten permission to visit Alpine, and learned the shortest way in. For Bill Schlicker did indeed own Alpine, but confirming that had been a task in itself.

Maps, Tax Records, and Research

After Great Northern day in Skykomish I had looked at the maps

in the Skykomish Museum and Bob Kelly had made a CD for me of old photos of

Alpine and included a 1922 map of Alpine from the Great Northern records. I also

had 2 topographic maps. The Green Trails map showed sections  but not the

corresponding section or township number. The National Geographic map that I have includes section numbers but not the townships numbers or range. On

Monday I began to find my way through King County tax records. From the maps I was reasonably certain that Alpine was in section 26, but I wasn't certain what township or range. I used my background as a real estate broker 40 years ago to guess that Alpine might be in Township 26 North, Range 12 East, Willamette Meridian. It turned out to be a good guess. There in the King County records was Alpine. It literally stuck out like a sore thumb. On the 1922 map of Alpine the area owned by the Great Northern Railway included a long diagonal connecting segment that met the railroad at one end and led to a diamond shaped parcel, centered on Carroll Creek, at the other. This was the water supply, certainly for the water tower for steam engines, and possibly for the town of Alpine as well. On the King County tax map this parcel is still the same shape. It is now identified as former Great Northern Railway right-of-way, and it is now owned by Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad,

but not the

corresponding section or township number. The National Geographic map that I have includes section numbers but not the townships numbers or range. On

Monday I began to find my way through King County tax records. From the maps I was reasonably certain that Alpine was in section 26, but I wasn't certain what township or range. I used my background as a real estate broker 40 years ago to guess that Alpine might be in Township 26 North, Range 12 East, Willamette Meridian. It turned out to be a good guess. There in the King County records was Alpine. It literally stuck out like a sore thumb. On the 1922 map of Alpine the area owned by the Great Northern Railway included a long diagonal connecting segment that met the railroad at one end and led to a diamond shaped parcel, centered on Carroll Creek, at the other. This was the water supply, certainly for the water tower for steam engines, and possibly for the town of Alpine as well. On the King County tax map this parcel is still the same shape. It is now identified as former Great Northern Railway right-of-way, and it is now owned by Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad,  among the thousands of parcels that BNSF has acquired over the years and probably has no idea that they own it or what to do with it.

among the thousands of parcels that BNSF has acquired over the years and probably has no idea that they own it or what to do with it.

This odd-shaped parcel of land cuts almost through the middle of tax parcel 2626129021. 2626129021 and its neighboring parcel 2626129012, and the former Great Northern Railway right-of-way, tax parcel 2626129019, are clearly the Town of Alpine. And it was here that I would find what I was looking for. According to King County records, tax parcels 2626129021 and 2626129012 both belong to Wilfred Schlicker of Startup, Washington. The information from Pat Casey and Ted Cleveland was correct. Unfortunately the tax records did not include an address or phone number. No listing in the phone book or on-line either. I would need to drive to Startup, to the little white church that was now an art gallery and rock shop, to find Bill Schlicker. That Saturday Bill wasn't in Startup. He had already left for his winter home in Rodeo, New Mexico, but his sister Mary Beth was working at the gallery. I told her about my Quixotic quest and she picked up the cell phone and called Bill. "I understand you own Alpine", I opened the conversation. "Oh", was the response on the other end. "Well that's what King County tax records say", I continued. "Then I guess I do". Actually Bill knew a great deal about Alpine and its history. Unfortunately he was in New Mexico. Unfortunately the key to the gate was with him. There was a gated road that I hadn't noticed. I had probably driven by it 50 times or more. Beyond that gate was the road to Alpine. It was still possible to drive into Alpine, but we wouldn't be driving in this year. I now knew the location, I had the property owner's permission to go on his property, and a walk of about 1 mile wasn't going to be a problem, even if the walk was virtually up the steep side of Mt Sawyer.

While doing the research to find the Town of Alpine, other interesting things had popped up. Glenn Forrest researched tax records and property maps. I was looking for cemeteries and information about Carl Clemans. There didn't seem to be a cemetery in Alpine; there also didn't seem to be a cemetery in Skykomish, although what is now called the Old Cascade Highway appeared to be called Cemetery Road on one old map dating to 1930. I thought that all towns have cemeteries. My mother was from Ridge, Montana (Population 2 in 2004) and the cemetery has 73 graves. It is difficult for me to imagine that Alpine, population 300?, and Skykomish, population 1000+?, didn't have cemeteries. Did they really transport bodies down the railroad to Sultan or Snohomish? Carl Clemans maintained a home in Snohomish before and after he owned Alpine. It seems natural that his son, Carl Lane Clemans, Jr. was buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Snohomish. Carl Jr died in 1908, when he was less than a year old, and his father was just getting the lumber company started in Alpine. But what about other individuals and other families - how did they handle the inevitable deaths. I don't yet know, but there is until now no evidence of a cemetery in Alpine or Skykomish. We know there were deaths because the names of those who died in Alpine are mentioned in the annual report given the attendees at the annual banquet in Alpine. Maybe it will be possible to trace the names in the annual report to places of burial, and then we will have an answer.

I haven't found a cemetery in Alpine, but cemeteries did turn up in unexpected places. I found a U. S. government record that listed a pioneer cemetery on 212th Street SW, just east of 84th Avenue W in Edmonds. The area is called Five Corners because 84th Avenue, and 212th Street meet the end of Bowdoin Way at an intersection that is a 5-way stop. My business is on the SW corner of 212th and 84th, with an actual address on Bowdoin Way. The cemetery must be within shouting distance of my store. I had never heard of a cemetery at Five Corners. There are 2 churches nearby and I assumed that the record must be talking about a church graveyard. I couldn't find (and I never have found) the U. S. Government record again, but I did find someone who knew about the existence of the graveyard. Steve Beck is a former president of the Edmonds-South Snohomish County Historical Society and the former owner of Beck's Funeral Home in Edmonds, Washington. Steve knew where the graveyard was and had a Polaroid photo from 1986 that showed 2 of the tombstones. The last burial appears to have been in 1953. It appears that construction may have occurred very near or on top of the old cemetery. While asking questions about the Five Corners graveyard, 2 different people mentioned an old graveyard that existed at the top of Dayton Street in Edmonds. Whether this graveyard is inside Yost Park or outside the park boundaries, under houses, is not known; there is less evidence for the existence of this graveyard, but it may be there.

Constructing on top of a graveyard seems unconscionable, but it does happen. It Seattle there is the notorious case of the Comet Lodge Cemetery. I remember my parents pointing out to me and my younger sister the pioneer cemetery on Graham Street in Seattle. We didn't know much about it except that it was not maintained, but you could see tombstones as you drove by. This may have been as early as 1953. According to http://www.worldperc.com/comet/faqs.shtml the last burial in the Comet Lodge Cemetery was of a 3-year old boy in 1936. Property disputes and disputed ownership claims, and careless supervision by the City of Seattle led to construction over as much as half the cemetery. It appears that the developer bulldozed tombstones, graves, and remains in the graves, and hauled everything off to the dump. Whether this also happened in my home town of Edmonds awaits further research. I was looking for a cemetery in Alpine, and haven't yet found one, and haven't found one in Skykomish either, which seems very strange, considering that a tiny place like Chiwaukum has a cemetery.

What I had found was a route into the town of Alpine, and I had permission to use it.

First Visit To Alpine

On October 9, 2008 the day arrived for me to visit Alpine for the first time. A few days before I had seen Matt Cawby's photos of Alpine on the new web page he had created. I already knew that we would find much more than 2 cornerstones. I was eager to finally enter Alpine and see just what we could find. Jackie Cuddy accompanied me and she was the photographer. The hike up the gravel road road from Highway 2 was very steep. I wouldn't have driven in my van even if we had a key to the gate. A 4-wheel drive is the only vehicle for this road. It was a cold day and the snow level was at about 2000 feet. The old Alpine depot had been at about 1800 feet elevation. The mill was at about the same elevation. The boarding house and liberty hall would be a few feet lower and the school about 40 feet higher. After walking less than 15 minutes we broke out into the clearing of the Bonneville Power Administration power line. An inspection road runs under the power line towers. The inspection road is little more than a 2 groove track where inspection vehicles drive in warm months, but it is in good condition and relatively level. The walking was easy as we turned west for about one-quarter mile. I completely missed the turn-off to Alpine although it was obvious what it was, but Jackie  noticed it and we turned uphill again. In less than 300 feet, 2 parallel ribbons of corrugated concrete told us that we had arrived. I only knew about old driveways in Seattle built this way. The road probably dated from the 1920s when concrete was too expensive to wastefully pour an entire road. The concrete was just the width of a truck's wheels. It was corrugated for traction, and it was only long enough to make the steepest part of the road into Alpine accessible to trucks. Above and below the steepest grade the road was dirt and gravel.

noticed it and we turned uphill again. In less than 300 feet, 2 parallel ribbons of corrugated concrete told us that we had arrived. I only knew about old driveways in Seattle built this way. The road probably dated from the 1920s when concrete was too expensive to wastefully pour an entire road. The concrete was just the width of a truck's wheels. It was corrugated for traction, and it was only long enough to make the steepest part of the road into Alpine accessible to trucks. Above and below the steepest grade the road was dirt and gravel.

Disappointment followed as we walked through abandoned vehicles that were clearly much newer than 1929. A second disappointment was that I realized I had left the map of the town in the car, and I wasn't going to go back to get it. We would have to wing it. I tried to visualize the map, but I wasn't very successful. Because we didn't have the map we walked right past the location of the mill and continued up to the BNSF railroad tracks. We did see a bridge across Carroll Creek. It looked too new to be of Alpine vintage. Months later I would learn for certain that the bridge was much newer than Alpine, but that the remains of timbers from the original wood bridge that had connected the mill and the boarding house area still lay crumbled, but not totally gone, in the cold waters of Carroll Creek under the newer bridge. I decided to climb higher to look for the water supply location along Carroll Creek. And we would be in the area of the school so we would look for that too.

At the railroad tracks we paused to listen and watch for trains. Eastbound trains are no problem. The diesels are at full load and there are usually 4 or 5 diesels pulling a train. The train is climbing a 2% grade, one of the steepest in the entire BNSF system and is traveling no more than 20 miles an hour. There is plenty of time to get out of the way. You can hear the train for at least 15 minutes before it gets to Alpine. I don't know how far the sound carries, but in Alpine the train is probably first heard at Foss River - 5 miles away. The sound may even carry all the way from Skykomish, which is 8 railroad miles away. It is the westbound trains that are just plain dangerous. Westbound the trains are coasting, braking against the grade, trying to hold speed down for the horseshoe bend at the Foss River trestle, which has been the site of notable derailments. Westbound trains are quiet. Even at low speed a train can be on you in a hurry. The railroad track curves just east of Alpine. A westbound train will be within 400 yards when it comes into view. A train cannot stop in 400 yards. The engineer's only option is his train whistle, and it is startling if you aren't aware of the train and aren't expecting the whistle. If you visit Alpine do not linger on or near the tracks. The relics to see in Alpine are not near the tracks and you shouldn't be either. A further reminder - Alpine is private property - please respect the owner's rights and don't go there unless you have permission.

Jackie and I crossed the tracks and began to climb the north slope of what I believed to be Mt Sawyer. We were on the west side of Carroll Creek, looking to see if any pipe or culvert from the water system was evident. Great Northern Railway diverted water from Carroll Creek above Alpine to the water tower which stood east of the Alpine depot on the south side of the tracks. Alpine only existed during the days of steam and steam engines needed huge amounts of water to make steam. As we climbed beside Carroll Creek we found broken sections of cast iron pipe, and decided that we had found what we were looking for. Actually we hadn't, but it was several months before we knew that. In general we were just wrong about everything we did in the first hour, and it was almost totally because of the initial mistake I had made by not bringing the map of Alpine. But we had fun. We could see immediately that there was more to Alpine than a pair of cornerstones.

We found cast iron pipe, and iron that looked like it had been from a roof. We found washtubs, and pails, and bottles with thick glass. Jackie photographed everything we saw and we put it back where we found it. I took only one picture and that was of Jackie. We gradually scrambled west along the slope, thinking that we would bump into the school. We weren't high enough on the side of the mountain. We did find what we first thought was the school, but either it was not the school or the school was smaller than we expected from the Alpine town map. Later we learned that it was not the school, but probably just a house. Gradually we descended the hill to the vicinity of the Alpine depot. At the location of the Alpine depot we found old bricks, some whole, but more often broken, and some associated not with the depot, but with more recent track welding. I paced off the distance to the bridge and it was exactly right. We had found the Alpine depot. In truth we shouldn't have been there; the location of the depot is on BNSF property and I didn't have their permission to be there.  About that time a train came drifting down the grade toward Foss River. The engineer whistled several times because we were too close to the track. When he realized that Jackie had situated herself to take a picture of the train the whistling stopped. We moved east along the railroad. Jackie found moss covered concrete. It was the foundation of the old water tower. I had walked right over it without recognizing it.

About that time a train came drifting down the grade toward Foss River. The engineer whistled several times because we were too close to the track. When he realized that Jackie had situated herself to take a picture of the train the whistling stopped. We moved east along the railroad. Jackie found moss covered concrete. It was the foundation of the old water tower. I had walked right over it without recognizing it.

The weather was cold. Snow was only about 400 feet above us. We were tired after scrambling in the underbrush for 2 hours. Fortunately the walk back to my car was downhill; we wouldn't have made it uphill. At the bottom we walked over to Alpine Falls on the Tye River. Once, a couple of generations ago, Alpine Falls  was a tourist destination. There was once a store at Alpine Falls. Now almost no one even knows the falls are there. There is enough parking for about 10 cars, but there are seldom more than one or two parked there. Alpine Falls is a beautiful sight. I don't know whether Alpine Falls was named first, or Alpine Creek - a mile west of Alpine Falls, or the town of Alpine, or the Alpine Lakes Region. The name seems suitable to all, but which was first? I don't know. I do know that the post office was named Alpine before the railroad depot. For a time the post office was Alpine and the depot was Nippon, but I don't know how the post office came to be Alpine in the first place.

was a tourist destination. There was once a store at Alpine Falls. Now almost no one even knows the falls are there. There is enough parking for about 10 cars, but there are seldom more than one or two parked there. Alpine Falls is a beautiful sight. I don't know whether Alpine Falls was named first, or Alpine Creek - a mile west of Alpine Falls, or the town of Alpine, or the Alpine Lakes Region. The name seems suitable to all, but which was first? I don't know. I do know that the post office was named Alpine before the railroad depot. For a time the post office was Alpine and the depot was Nippon, but I don't know how the post office came to be Alpine in the first place.

We decided not to walk to the base of Alpine Falls and climb up again. That was a good decision. I did that walk a week later when I hadn't gone into the town of Alpine, and the amount of energy it took to climb back up from the base of Alpine Falls would probably have killed me after hiking around the town of Alpine for 2 hours. If I was going to spend much time in Alpine I would need to get into better shape.

From the photos that Matt Cawby had posted on his web site, we knew that there was a lot of the town of Alpine that we hadn't seen. After examining the map that night I was certain that Matt, his dog Keesha, Jackie, and I had only wandered over about 20% of Alpine. There would be more remains of buildings and other relics to find when the snow was off again. That might be 6 months or more. It snows in Alpine; it snows a lot in Alpine, which is why everything seems to be named Alpine in the area. I didn't own a 4-wheel drive or a snowmobile. I wouldn't be going back to Alpine for many months, and another winter would do its work to destroy the remains of the town. We left whatever ghosts might be in that little town that I had sought for 3 months, and headed back down the Tye/Sky valley to Skykomish. As is now my custom when in Alpine or Wellington, we stopped at the Cascadia Inn in Skykomish to enjoy a Cadia burger before driving back to Edmonds. I think Jackie ordered something smaller, but I was hungry and tired and a Cadia burger sounded just about right. It wasn't a time to worry about cholesterol or calories.

I had visited the little ghost town of Alpine after 3 months of looking for it. I had already visited Tonga and Skykomish. The next Great Northern Railway Station would be Miller River/Berlin about 2 miles west of Skykomish. I had visited Alpine and I could be finished with it as I was finished with a dozen other stations. Not that I wouldn't ever go back; I had been to Wellington at least 6 or 7 times, and I had been to Cascade Station at least 3 times. I could go back, but I could also go on, except that Alpine was tugging on my spirit. There was unfinished work for me in Alpine and I found I really couldn't go on. It was because of Carl Lane Clemans. Clemans maintained his home on Avenue C in Snohomish before, during, and after Alpine was occupied, but he is inseparable from Alpine and Alpine is inseparable from him.

Both Clemans and Alpine have been almost lost to history. In a few places only the memory of Clemans remains. In Snohomish, Washington the Clemans house at 315 Avenue C is recognized as one of the historic houses of Snohomish. Sigma Nu Fraternity recognizes Clemans in its Hall of Honor; Clemans was inducted in the inaugural class of inductees to the Sigma Nu Hall of Honor in 1948. Most notably Clemans is remembered in the Emma Lord series of mysteries written by Mary Daheim. Most of the books in the Emma Lord series take place in Alpine, home of the Alpine Advocate newspaper,and Carl Clemans is mentioned in several of the books. And last, if you dig deeply enough in the sports histories of Stanford and the University of Washington you will find the name of Carl Lane Clemans and a few very brief memories of his football career.

The Remarkable Carl Lane Clemans

I couldn't go back to the town of Alpine for a while, but I could continue to research the town and the man who is so intertwined with the history of the town of Alpine, Carl Lane Clemans. The first things that I read about Carl Clemans made him appear to be a true saint. Those depictions may be exaggerated, but I have discovered that Carl Lane Clemans was a unique and remarkable individual, with flaws like the rest of us, but with outstanding characteristics that made him stand apart.

Carl Lane Clemans was born in Manchester, Iowa. 7 Mr Clemans attended Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa. Clemans maintained an attachment to Cornell College for all of his life. "Alpine made famous" 8 when on July 18, 1925 a number of alumni of Cornell College celebrated together in Alpine, and picnicked at  Star Lake. Clemans' daughter, Kate, and his wife, Harriett, attended Cornell College in the 1920s. According to Sigma Nu fraternity, Clemans founded the Sigma Nu chapter (Chi) at Cornell College, the first of several he would found. According to Cornell College records, Clemans earned a B Ph at Cornell in 1888.

Star Lake. Clemans' daughter, Kate, and his wife, Harriett, attended Cornell College in the 1920s. According to Sigma Nu fraternity, Clemans founded the Sigma Nu chapter (Chi) at Cornell College, the first of several he would found. According to Cornell College records, Clemans earned a B Ph at Cornell in 1888.

From Cornell College Clemans traveled west to Stanford in 1891, when that school opened. At Stanford Clemans also left his mark on history, at the university and on the football field. Clemans participated in the first inter-collegiate football game ever played on the West Coast of the United States. Clemans scored the winning touchdown as Stanford upset favored Cal, which had fielded a football team for ten years and was physically heavier. In November 1954, Sports Illustrated wrote about March 19, 1892, the eventful day when Stanford and Cal met on the football field for the first time in the very first "Big Game" of the 120-year rivalry. By all means read the marvelous Sports Illustrated article. Unfortunately I don't know who wrote the SI article, but, if you don't pause to read it, the essence of the story follows. Clemans role in the game is variously reported, but it appears that he was the star. The winning cheer was reputedly,"Then shout the grand old Stanford yell, we've sent her through the goal! Berkeley's line looked solid, but Clemans found the hole." 9 The team manager for Stanford was apparently quite persuasive. He talked a San Francisco sporting store owner into providing the new Stanford team with uniforms although there was no money to pay for the uniforms unless enough tickets were sold. The Stanford and Cal managers managed to rent Haight Street Grounds baseball park on the same terms. The owner would be paid when the fans paid to see the game. Ditto for the company that printed the tickets. On the subject of tickets, 5000 were printed, which suggests that the team managers were wildly optimistic or incredibly shrewd in measuring fan interest. My research indicates that a crowd of 2000 for a football game in 1892 was a huge crowd. The cost of the ticket to the first "Big Game" was 2 dollars, a day's wage. But nearly 10,000 bought tickets and saw Stanford upset Cal. The persuasive Stanford team manager was a fella named Herbert Hoover, Stanford Class 1895.